Activity Management

Why do pacing?

If you consider your energy as a battery, you may feel that your battery does not charge itself efficiently over night. Also, it does not hold its charge as well in the day. The aim of pacing is to look after your battery and avoid running it flat: always leaving something in there!

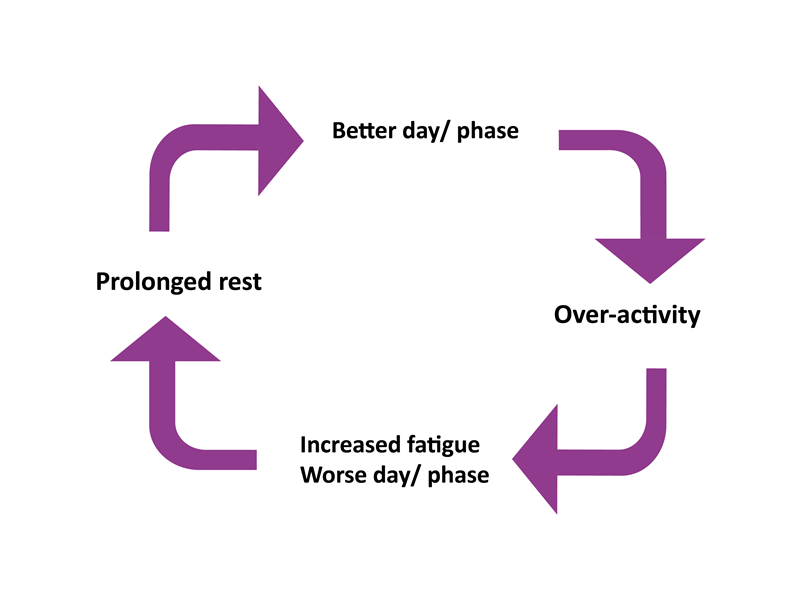

Many people find that they have slightly better and worse days. On a better day, people are often more physically and/or mentally active and they may tackle things they are normally unable to do.

- When people tackle too much on a better day/days they can unintentionally run their battery flat.

- It can then take a while for them to re-charge the battery whilst their body forces them to recover.

- Once the battery has some charge in it again, this can result in them ‘overdoing things’ which in turn leads to feeling worse, and the cycle continues of better and worse days. We refer to this as ‘Boom and Bust’.

What is pacing?

- A long-term method of managing daily activity to balance your rest and activity needs.

- It is NOT an exercise programme or a forced regime

- Helps you to move into a stable phase (see section 8 on moving forward), achieve more activity, and gain control over your condition in the long run.

How to do pacing?

1) Get your head round it:

- Pacing recognises that every activity we do in a day uses energy whether this is physical, mental or emotional. Demands on our energy come from different sources such as family, work and other responsibilities.

- Pacing involves taking short and frequent rests around every activity. This is also important on better days when you may feel you do not want to stop or need to.

- Pacing involves not over-doing things or pushing beyond your limits. It involves stopping before you have reached your limit in order to achieve a more sustainable and consistent routine.

- Pacing is not about cutting out activities but may involve considering what you do, how you do it, and how long you do it for. eg. it may mean doing things for less time, spreading tasks out and breaking tasks into smaller chunks.

- The charity Action for ME has a good booklet on ‘Pacing’ available to read on their website or buy if you would like a hard copy (afme.org.uk).

N.B. it is also important not to ‘under-do’ things. The less we do, the more fed up and frustrated we may feel and we can end up in a vicious cycle whereby we are fatigued if we do things but equally fatigued if we don’t.

2) Self-monitor:

Keeping a diary can be a useful way to look at your routine and understand how what you do affects your fatigue and other symptoms.

It is important to become aware of the things that may ‘set you back’ so you can review the way you do them. Ask yourself if there is an easier way in which something can be done.

3) Implement:

Rests need to be timetabled into each day, regardless of symptoms, so that they become a consistent part of your routine. They should be spread throughout the day, regardless of symptoms, in small, frequent chunks around every activity. Initially it may be difficult to accept the notion of these rest breaks. However, intermittent rest can save energy for other tasks. The next section talks more about rest.

Top Tips

Acceptance of your condition is an important starting point.

Stop and rest before your body forces you to.

Frequent short rests are of more benefit than fewer longer rests.

When completing tasks, the calmer the better!

Don’t feel bad if things don't always don’t go to plan.

Some people find it useful to structure each day/week to include rest time and make others aware of their plans.

Set alarms or alerts to remind you to rest.

Remember you can also pace at work or when out of the house.

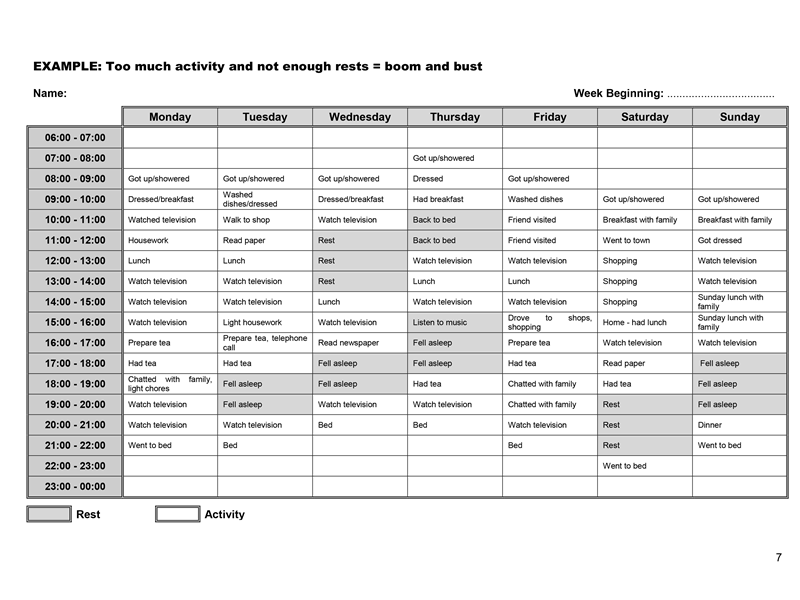

1. Boom / Bust

Most people have good and bad days/phases.

They alternate between doing too much on a good day and then being severely limited on a bad day in order to recover.

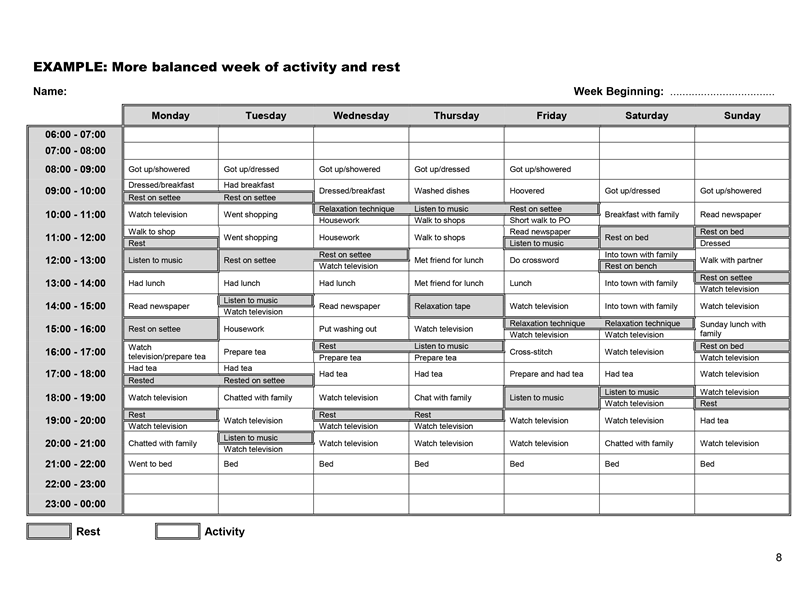

2. Stable Phase (baseline)

By pacing yourself, you can better achieve a consistent and manageable balance of rest and activity each day.

The aim is to achieve a daily routine that can be maintained over a longer period of time and reduce/eliminate the boom-bust pattern.

Know your limits and stop before you have done too much. Everyone is different. Listen to your body.

Do not expect to feel better immediately as this is a long-term way to manage ME/CFS and the goal is to find a sustainable routine that suits you.

Here are some examples of activity:

(Click image to expand)